New Study: Vitamin Supplements May Not Slow GA Growth in Advanced Macular Degeneration

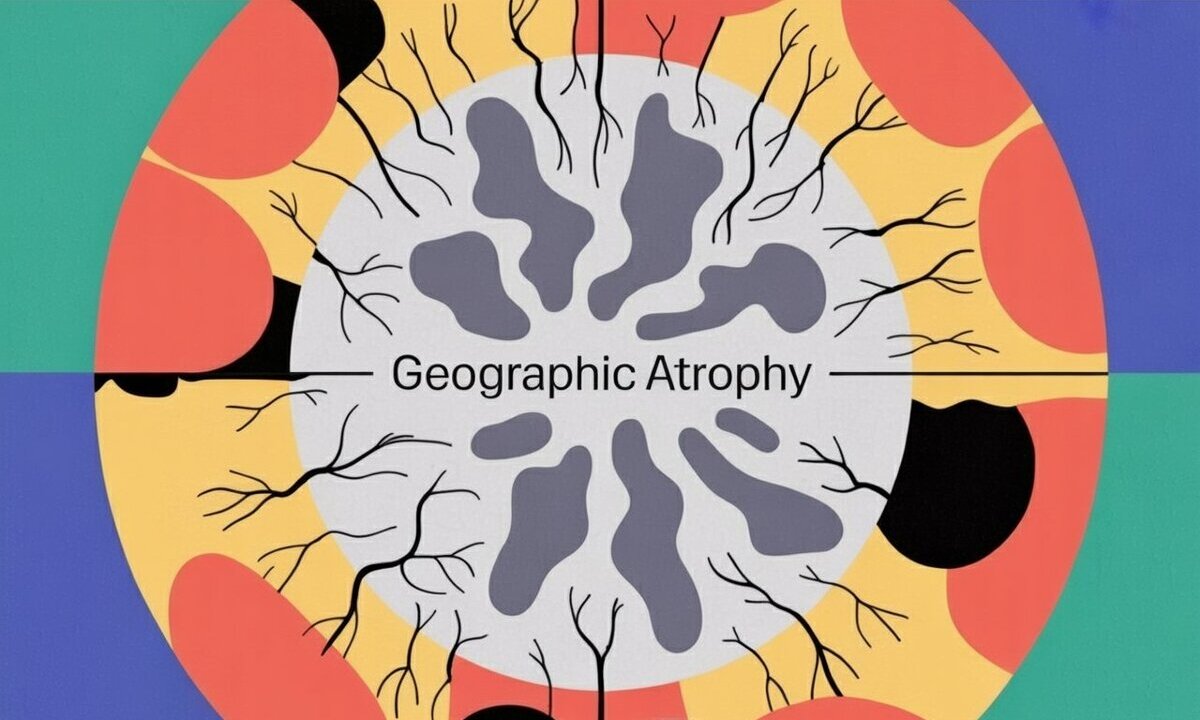

For years, ophthalmologists have recommended AREDS vitamins to patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), based on landmark studies suggesting the supplements slow progression to late stage forms of AMD. Earlier this year, an analysis of those studies, AREDS and AREDS2, found that antioxidants and vitamins slowed geographic atrophy (GA) progression toward the central macula in patients with advanced AMD. However, a new study using multimodal imaging refutes these claims.

The researchers presented their findings at the 129th annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

The original AREDS study, launched in 1992, and its successor AREDS2, begun in 2006, represented major breakthroughs in preventing advanced forms of AMD. They showed that vitamin supplementation could significantly slow progression to wet macular degeneration, the more treatable form of advanced disease, among high-risk patients.

But the studies found no benefit for geographic atrophy, the "dry" form of advanced AMD that accounts for roughly half of severe vision loss from the disease.

Then in a recent reanalysis combining two of the AREDS studies together, researchers led by Keenan and colleagues reported something unexpected: among patients who already had geographic atrophy, AREDS vitamins appeared to slow the condition's progression toward the fovea—the critical area responsible for sharp, detailed vision—by 22 to 34 micrometers per year.

That finding generated considerable interest in the retina community. But it also raised questions, given that the original studies had used color fundus photography, an older imaging technique, to measure disease progression.

Those questions prompted Rishi P. Singh, MD, incoming chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at Mass Eye and Ear and Mass General Brigham, and colleagues to reexamined data from OAKS and DERBY, two recent trials testing pegcetacoplan, one of two drugs now FDA-approved for geographic atrophy. These studies included more than 1,200 untreated eyes and employed state-of-the-art imaging: fundus autofluorescence and optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Far more precise measurements of geographic atrophy

The modern techniques allow far more precise measurements of geographic atrophy than were possible in the 1990s and 2000s. Critically, the newer imaging methods are now the standard accepted by regulatory agencies for evaluating treatments.

The results were unequivocal. The researchers found no significant effect of AREDS or AREDS2 supplementation on overall geographic atrophy growth. They also found no effect on progression toward the fovea—directly contradicting the Keenan analysis.

"We were quite surprised," Dr. Singh said. They believe the previously reported benefit may have been an artifact of the older measurement techniques, though differences in study populations and duration could also play a role.

An independent analysis of AREDS supplements using data from two other clinical trials, CHROMA and SPECTRI, came to the same conclusion.

The finding takes on added significance now that two FDA-approved treatments—pegcetacoplan and avacincaptad pegol—have been shown to slow geographic atrophy progression. These drugs, delivered by injection into the eye, offer the first proven therapies for a condition that affects more than five million people worldwide.

For the public, researchers advise caution. "Until there's more data like from a prospective randomized clinical study, we don't know if antioxidants and macular pigments like lutein have beneficial effects on geographic atrophy," Dr. Singh said, while encouraging patients to discuss the newly approved treatments with their doctors.

Source: American Academy of Ophthal